Marathon #10: East Canyon Marathon

I ran the East Canyon Marathon in Morgan, Utah last weekend. This race had some significance to me being marathon #10 and my first in-person marathon since October 2019.

Each marathon that you run is an entirely different experience. I’m always experimenting and learning more about myself, my limits, and my body during races. I dive into my experience running the East Canyon Marathon, and a few other topics below in my blog post:

- How fueling both with UCAN gels and HVMN Ketone Esters helped me feel strong for the race

- Why training miles matter, and why they don’t

- Running in poor air: My decision to run wearing a KN95 mask

- PurpleAir vs AirNow and my AQI threshold for not running outside

- Comparing HR data for half-marathons, marathons, and ultramarathons

- Why I carbo-loaded for this race

- The diminishing returns of fueling

- Interpreting my CGM (continuous glucose monitor) data from the race

- Muscle imbalances, possibly due to boxing

- The fluid nature of goal setting during marathons

- The ideal cadence for running

Repaying the Favor: Running Scott’s first marathon

This race was special because I got to repay the favor to my good friend Scott. During my 2nd marathon on my 27th birthday, Scott ran the 10K and then came back and biked alongside me and provided a ton of support. So I was happy to be there for him doing his very first marathon, in a place special to him where his family lives and along a course he’s biked several times.

Overall race:

The East Canyon Marathon is the 9th fastest course in Utah. While you have to deal with some elevation (7,429 ft) at the start, the race declines 2,500 feet down to Morgan. But don’t be fooled by the overall decline, there’s still 790 ft of incline in the race. The race starts at 6AM, before sunrise, and you run Big Mountain Pass at the top of Emigration Canyon down to Red Rock Canyon and finishes at the Morgan County Fairgrounds.

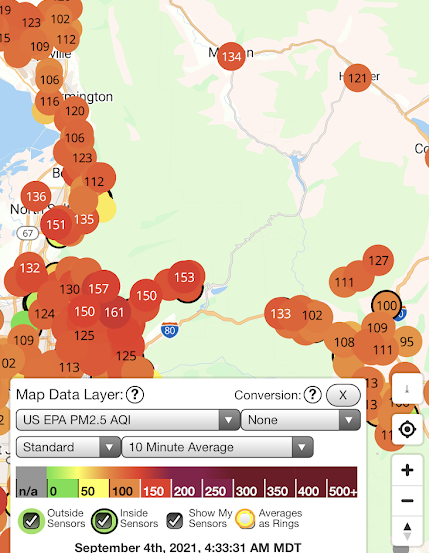

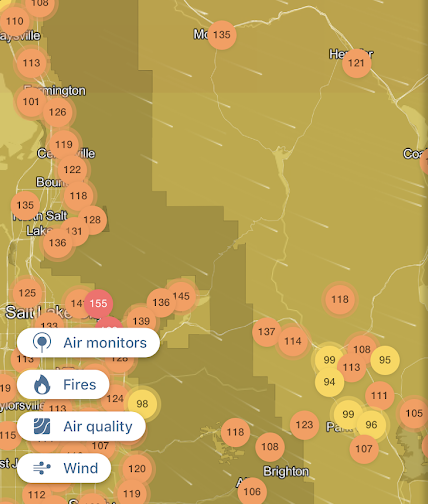

Air Quality

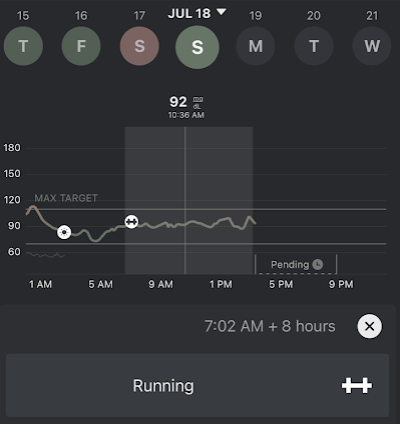

Scott and I were monitoring the air quality prior to the race, and we set our thresholds for when we would pull out of the race. We told each other that if the AQI was above 150 we would drop out of the race. I quietly thought that anything above 120 would be pushing it.

In the morning, the AQI showed up as 135. I made the decision at that point to run with a KN95, which isn’t the most comfortable thing to wear while running. I expected myself to take it off at some point during the run if it got uncomfortable, but wanted to limit my exposure to running in bad air to under 2 hours. So that meant that at least the first half of the marathon would be run wearing my mask.

Comparing Air Quality Metrics

AirNow and the Apple Maps Air Quality metrics are significantly lower than PurpleAir and IQAir. I know that PurpleAir has far more sensors than AirNow, but am still not sure why the discrepancy is so big. I conservatively only rely on PurpleAir and IQAir.

During training, I don’t even run outside if the AQI is above 100. Sometimes even lower. That can flare up a chronic cough I have and I always play it safe by running inside on a treadmill instead.

Running downhill in the Dark

As you can see from the elevation chart, it’s a pretty nasty downhill to start the race. I had a weird dream a few months ago of me running down a steep decline in pitch black darkness. It was surreal running through the night, straight down a steep mountain, hardly being able to see anything other than the moon, the stars, the outline of the mountains ahead, and a few silhouettes of the runners in front of me.

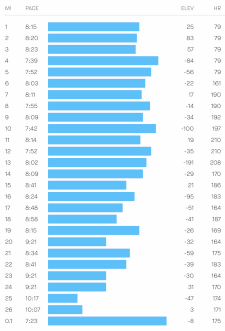

I ran with the 3:30 pacer to start the race, like I did during my PR race, the Mountains 2 Beach Marathon in Ventura, CA. I thought with the decline, I could adopt a similar strategy of running a 1:45 first half and a 2:00 second half. But through the first quarter of the race, the 3:30 pacer ran a 3:00 pace, presumably because of the steep decline. We were flying to start the race, with me running the first 6 miles in under 45 minutes.

Running that fast, that early, down that steep of a decline was interesting. It’s hardly a way to warm-up, and my legs were still frozen but I could tell my knees were pounding on the road as I kept pace going downhill. I felt the impact on my quads as early as mile 4, and some tightness in my right hamstring as well. That came back to haunt me later.

Aid Stations

For a small race, I was happy that they had aid stations every 2 miles. Some of the race reviews complain about the organization of the race, but knowing that it’s a small race (<300 people), I wasn’t expecting anything like what you see at a major marathon. I also realized how little I really need, and how thankful I was to have volunteers giving us water.

The Deceptive Inclines

The sun started to rise about an hour in and you can appreciate the views. Once you hit mile 11.5, you see a steep incline that most people have to walk. It’s easy to overlook that incline on the elevation map, but that really says more about the steep decline at the start than the incline at mile 11.5. There are actually quite a few rolling hills after mile 4. We didn’t realize until after the race, but there was quietly 790 ft of incline, which is a decent amount of uphill for a road race.

I didn’t capture much footage during the race, but thankfully Scott had my camera and took a lot of videos describing his experience of the course and running his first marathon (primarily training by biking due to injuries!).

The fluid nature of goal setting

Every race, my goals are constantly re-evaluated and re-assessed at various mile markers where I have to make decisions on how to strategize the rest of the race. With more experience, I’ve become more familiar with the points of the race where I have to make decisions on whether I dig deep or hold back. And while every race I start with an ambitious goal (i.e. a PR or a BQ), I also have sub-goals if my plan-A doesn’t work out.

My decision tree really started with one benchmark – to hit a 1:45 first half. If I could hit that, I would shoot for a PR (my “best-outcome goal”). If I didn’t, I would pull back and shoot for a 4:00 time. Meanwhile, Scott was shooting for a 4:00 marathon as his “best-outcome goal”, with his secondary goal being just to finish. So I hoped to pull back and maybe he would catch up and we could finish the marathon together. I finished the first half in 1:47, and after re-evaluating how I felt, made the decision to shoot for a 4:00 marathon.

Starting Too Fast: The Repurcussions

By mile 16, my quads were shot and I could hardly pick them up. But considering my past races (including my PR race) I had to deal with cramps, I was pretty happy to never experience them during this race. I felt strong otherwise, but my quads were just not co-operating with me. Even as I write this, three days later, my quads are still sore while the rest of my legs feel okay. This is different from other races where the pain is evenly distributed across my calves and hamstrings. My form changed to a much slower jog where I could hardly pick up my feet.

The Final Push

The final 4-ish miles are through Morgan and relatively flatter. I started to slow down and thought maybe Scott would catch up, but he ended up being further behind. The East Canyon Marathon is a smaller race that doesn’t track racers at various splits, so I had no idea where he was. Maybe we could’ve shared our locations on our iPhones, but we never really planned that. I ended up finishing with a time of 4:10, which is a middle-of-the-pack result, my 4th best time out of my 10 marathons. Scott ended up finishing at 4:44 and I was able to do a final-sprint with him to the finish.

Strategy and reasoning behind it:

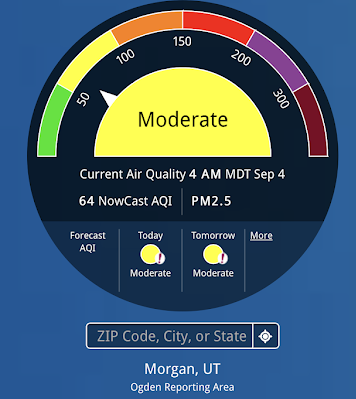

Heart Rate Data:

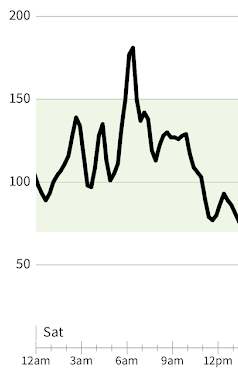

After my Big Chief 50K ultramarathon, I wrote about how I keep my HR below 152bpm for ultras. That seems to keep me in an aerobic state the entire race and is the reason why I feel that 50K’s are easier than marathons. The reason for keeping my training runs and ultras at a lower heart rate stem from me trying to stay outside of the black hole of heart-rate training. I also think that chronically elevating your heart rate to Zone 4 for races is not great for long term health, so I’m very particular of how often I limit my hard efforts.

Marathons require a different strategy since you’re pushing for time. I really don’t think running at Zone 4-5 for 4 hours is too healthy. But on the other hand, I only run 1-3 marathons a year, so it’s okay to push it a little on those days.

I found this pretty interesting to compare my heart rate data between half-marathons, marathons, and ultras:

- Half-marathon PR: 1:36, 183bpm average, 210bpm max

- Marathon PR: 3:42, 162bpm average, 210bpm max

- East Canyon Marathon: 4:10, 159bpm average, 210bpm max

- Big Chief 50K: 6:59 moving time (7:30 with stops),148bpm average, 191bpm max

I’m pretty happy with where I kept my heart-rate, but find the data fascinating. It also shows why half-marathons are so painful, with me running at 183bpm for an hour and a half. Marathons are a humbling distance, where you can’t just crank out a great time if you go out too hard.

Monitoring glucose levels (Race Fueling):

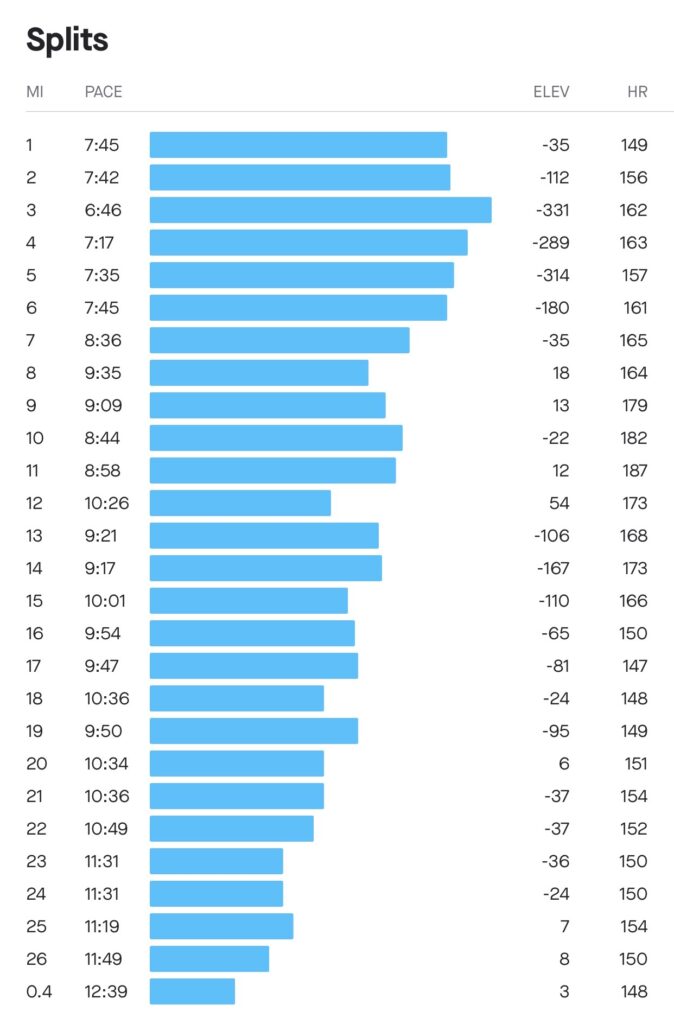

Similar to the Big Chief 50K ultramarathon, I monitored my glucose levels. But unlike the Big Chief 50K ultramarathon, I did not use the same strategy or keeping glucose flat or even monitor my glucose during the race.

Ultramarathons are a different story for me, being more about completing the race than achieving a PR. Marathons are about time. The East Canyon Marathon I had performance goals, and was a race I was willing to carbo-load for and fuel more extensively with UCAN and gels. I expected more fluctuations in glucose and higher overall levels, so there was a bit more pre-emptive loading than reactive loading. With my goal to stay aerobic the entire ultramarathon, I actually didn’t even really need to fuel at any point during that race. But with my goals for a faster pace and faster time for this marathon, I was totally okay with my blood sugar hitting higher levels.

In addition, I simply didn’t want to pull my phone out for any reason during the race. So my CGM didn’t factor into any decision making, but more so provided data after the race for me to interpret.

Analyzing my CGM data:

My blood sugar peaked at 180 at 6AM when the race started and hit 140 several times after fueling. This is far different from my chart during the Big Chief 50K ultramarathon, where I kept my levels between 90-100 the entire race.

My fear of getting on the blood sugar rollercoaster is the body’s tendency to overreact, dumping insulin into the bloodstream and blood sugar dropping into bonking territory. Peter Attia talks about how fast blood sugar spikes lead to crashes on this podcast. Luckily, I didn’t experience any hypoglycemic events and my blood sugar never went below 100.

Ideal Glucose Levels:

This was where I had to play around. Looking through the Supersapiens Athletes Facebook Group, I notice many athletes have an ideal performance zone above 160, or even higher. Many athletes swear by these higher readings, which I tend to think are too high. For overall health, Levels recommends keeping glucose levels ideally below 110. But as I’m here to experiment, I was a little looser on my glucose peaks and started loading up. As you can see, my levels were more likely to hover at 140, rather than 160. But at some point, I can’t imagine how having more fuel would help (more below).

Imbalances – All on my right leg: Is this from Boxing?

I’ve noticed this for a while, but all of my injuries and muscle soreness occur on my right leg. At mile 4, I felt my right hamstring tighten up, and within a few miles I felt my right quad get tired. It seems like my right leg does a lot more work, and I’m not exactly sure why.

In boxing, I fight in an orthodox stance, which has me sitting back on my right foot. Although I don’t compete anymore, I’ve been training for 16+ years. I wonder if that has anything to do with my right leg injuries..

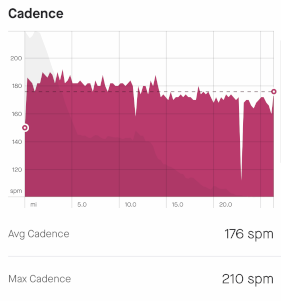

Cadence:

This sometimes gets overlooked, but it’s best to keep a cadence of 180 steps per minute.

Pre-race: Training and Fueling

Training miles:

My training this year has been like clock-work, running 5K/day 6 days a week and one 10+ mile run on Saturdays. I stick to ~30 miles per week and don’t have the availability to run more.

It’s interesting to see how more mileage helps, and how it doesn’t. I ran my marathon PR at a 3:42 when I was running 20 miles a week, but ran the last half of that marathon waddling through some pretty bad cramps. Now, running 30 miles a week, I felt strong, never cramped, but ran a 4:10. The additional distance per week and consistency helped a lot. But perhaps I wasn’t actually as fast this time around. Or maybe the course played a factor, or my quick pace out of the start.

Fueling (Night-Before):

Yep, I carbo-loaded again. My carbo-loading is literally just the night before, not 3 or 6 days prior to a race like others do. I stay relatively low-carb the entire week before my final dinner being a carbo-loading meal. If I were to carb-load 6 days in a row, I’d probably gain 10-15lbs before the race. Runners World suggests I should eat 2,400 calories of carbs per day as a carbo-load – that is terrible advice, not just for racing but for overall health.

That being said, the night before I did what’s becoming my routine carbo-load – Pad Thai.

Day-Of Fueling:

Primary source of carbs:

Gen UCAN: I use UCAN as my slow-burning source of carbs that does not spike and crash blood sugar.

- Use code UCANREFHNP4YHJXR6 for $25 off

Fuel:

- 1AM-3AM: I slowly sipped on the following drinks in the morning before leaving the house at 3:30AM to catch the shuttle to the race, which left at 4:30AM.

- UCAN Superstarch – 2 Scoops

- UCAN Energy Bar x 2

- Kion Essential Amino Acids

- Vital Protein Collagen Protein

- FITAID

- 5:30AM:

- 1/2 HVMN Ketone Ester

- 1 UCAN Gel

- 6:00AM: Race Start

- 7:30AM: About halfway through the race

- 1 UCAN Gel

- 1/2 HVMN Ketone Ester

- 9:00AM:

- 1 UCAN Gel

- 9:45AM: Almost finished

- 1/2 HVMN Ketone Ester

The Diminishing Returns of Fueling

This is something I’m still trying to wrap my head around. Why do we care so much about fueling? Why do people take Gu Packets every 1-2 miles? Yes, we need to fuel ourselves to train, but why every mile when we already have high glucose levels? Does that extra sugar bomb, when we already have plenty of fuel, actually make you faster? I really won’t have any answers until we start seeing top athletes share their CGM data. I can tell you, though, that at mile 20 that my legs felt heavy because my quads were actually not strong enough, not because I didn’t fuel enough.

My fueling at 1AM must have spiked my blood sugar. Once again I only had 3 UCAN gels the entire race, but had high glucose readings the entire race. I can’t imagine how having 9 more would have magically made me run faster.

Final Thoughts

This is marathon #10, but I feel like each race provides its own unique insight into my body. After a streak of linear growth, improving my PR race after race, I have my good days and bad days. Not every race needs to be a PR. And even on this middle-of-the-pack result, it felt a lot more comfortable than prior races.

This race is a reminder that there are a lot of variables that go into performance. Training miles, fueling, cross-training, mobility, and race conditions all play a role into how your race goes. If you train 20 miles a week, but incorporate speed work and intervals, your race may look a lot different than running 50 miles of steady state runs. The weather or the conditions may change. Pacers may go out too fast. Every race will be entirely different. I’m just trying to enjoy and learn from each one.

Suggested Podcasts:

Subscribe to my newsletter!